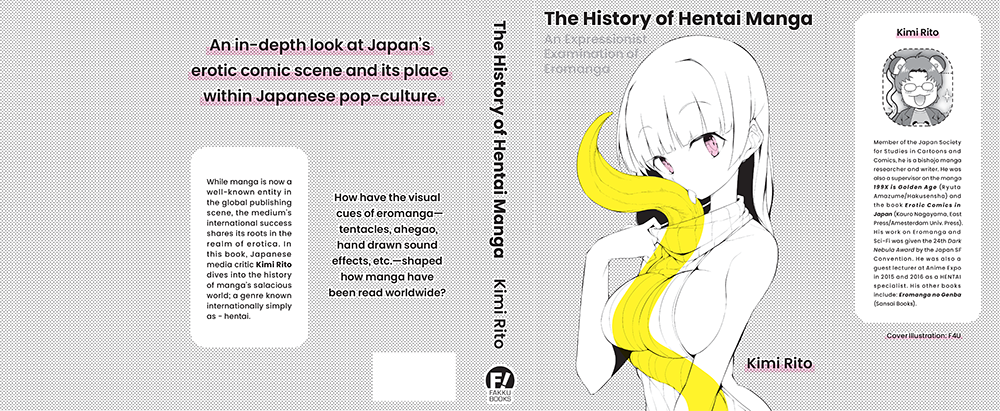

[Kimi Rito] The History of Hentai Manga

5

Brittany

Director of Production

An in-depth look at Japan's erotic comic scene and its place within Japanese pop-culture!

While manga is now a well known entity in the global publishing scene, the medium's international success has its roots in the realm of eros. Japanese media critic Kimi Rito dives into the history of manga's erotic world; a genre known internationally simply as - hentai. What are the origins of hentai? How has it evolved from the days of ukiyo-e to today's modern comics and animation. Who are the people making hentai? And who are the people reading these works? And what is the medium ultimately trying to express beyond sexuality? Rito looks at the content from a number of perspectives covering everything from the indie comics scene (doujinshi) to how hentai's symbolism has extended far beyond Japan and its comics industry.

Release Dates

Pre-Order - December 7, 2021

Digital - October 26, 2021

Paperback - [Pre-order now on Amazon!]

Buy Digital Now!

While manga is now a well known entity in the global publishing scene, the medium's international success has its roots in the realm of eros. Japanese media critic Kimi Rito dives into the history of manga's erotic world; a genre known internationally simply as - hentai. What are the origins of hentai? How has it evolved from the days of ukiyo-e to today's modern comics and animation. Who are the people making hentai? And who are the people reading these works? And what is the medium ultimately trying to express beyond sexuality? Rito looks at the content from a number of perspectives covering everything from the indie comics scene (doujinshi) to how hentai's symbolism has extended far beyond Japan and its comics industry.

Release Dates

Pre-Order - December 7, 2021

Digital - October 26, 2021

Paperback - [Pre-order now on Amazon!]

Buy Digital Now!

2

luinthoron

High Priest of Loli

So essentially a longer version of Hentai Manga! A Brief History of Pornographic Comics in Japan? Sounds great!

1

Brittany

Director of Production

luinthoron wrote...

So essentially a longer version of Hentai Manga! A Brief History of Pornographic Comics in Japan? Sounds great!Not quite the same, this book focuses more on the semiotics of the symbols in ero manga (the ability for someone to look at something and immediately understand it) that have stuck within ero manga - where they came from, why they appeared - how it impacted other genres, etc.

It's a real fascinating read!

1

erolover

Ero Maniac

It's nice to finally see this get released as it's something I'm really interested in reading. I can't wait to get my physical copy.

3

shibby06

Hentai Aficionado

This is still currently a work in progress (I've not finished the book as yet), but here are some of my initial thought on each chapter:

Chapter One: Th Evolution of Breasts

Chapter 1 cover the evolution of breast in gekiga works in the 70s, bishojo and lolicon works in the 80s, and then finally into how kyounyu and its various other forms began to take over through the late 80s, and which seemingly culminated in the early 00s. Honestly, it was a pretty interesting chapter. I particularly like the idea of there being kyounyu researchers out there and that the lolicon fundamentalists fought the ero-supremacists over the direction of the medium — totally has ero-opera vibes. It was also pretty interesting to see how—as Kyounyu evolved through the 90s and early 00s—just how many legendary artists who started back then, are still around today; Distance, Yumisuke Kotoyoshi, and Miyabi Tsuzuru to name a few. As well as, just how much we owe to the likes of Kei Kitamimaki and Tohru Nishimaki, who were really the pioneers of kyounuu way back when. The level of influence they've had really can't be measured, particularly Kei Kitamimaki who I've always felt has been underrated. I mean, if it weren't for him, we might never have got marumiya, who is without a doubt, my favourite futanari artist.

Chapter Two: The Dragonball Nipple

Chapter 2 cover the origins of the now-ubiquitous "Nipple Afterimage technique" and how it's become such a dominant tool in an artist's toolkit to convey motion. It's a pretty long chapter if I'm honest, and quite the slog to get through. There are two interviews with the creators of the technique; Hiroya Oku - the creator of Gantz and Hiroyuki Utatane - the creator of Countdown: Sex Bombs. Oku's interview is quite long and you get a certain sense of, firstly; deja vu within similar questions or answers being given, and secondly; a sense that the author is overthinking things somewhat. Coming up for air on the other side though, you then get a rundown of the evolution of the technique from 1988 to the present day. Personally, I'm not really a big fan of the earlier interpretation of the afterimage. In my mind, it only really got good around the early 00s.

Chapter Three: Censorship be damn, you cannot stop the tentacle!

Chapter 3, though short, delves into tentacle rape/play and how the birth of this trope is directly related to Japan's censorship laws. It's probably one of the better chapters. I particularly liked the interview with Toshio Maeda, who I think needs no introduction. Their discussion on the practice of censorship in Japan was interesting, although I was surprised and less than convinced with their argument for maintaining the practice (pg 151). That aside though, following the interview, we get a rundown of the evolution of the trope. From its initial boom in the 80s to its 90s decline, and then its resurgence in the 00s. Hopefully, FAKKU might pick up some tentacles books in the future.

Chapter Four: The confusing history of the cross-section or is it x-ray view?

Chapter 4 covered the cross-section view trope, though rather confusingly. At the start, the author explains the difference between the cross-section, as you might see in a medical journal, and the x-ray or transparent view, as they called it. However, they then go on to show examples of the x-ray view but refer to them as cross-sections, which muddies the waters. That aside though, the history and evolution of the two had some interesting moments. Again it was pointed out that the cross-section view came about to circumvent censorship by framing it as educational and using it predominately for comedic effect. Later in its history, it was adopted into ero-manga, with guro artists taking it to the extreme, whereas less niche genres were more restrained and balanced it more with the x-ray view. The real highlight of the chapter though was the interview with John. K. Pe-ta, who I think straddles the fence between guro and pretty. Honestly, I really enjoy his artwork but at the same time, it can be pretty distressing. It's one of the reasons why his books always start with Monzetsu, which means 'comfy agony'... you can't say he isn't warning people.

Note: in chapter 8 (foreign impact), the author clarifies that what the Japanese call the cross-section view, Americans or westerners call the x-ray view. You may read the chapter and be slightly confused, as I was, but just know it gets clarified later. Personally, I still think their idea of a cross-section view is wrong. To me, you need to have a clear axis that you're slicing down/across. If you're just peering into an object, that to me is just transparent or x-ray.

Chapter Five: Ahegao Face—you either love it or hate it

Chapter 5 covers a topic I think most people would have some interest in, simply because of how it's transcended the medium, going on to have widespread global use. If it wasn't obvious enough already, I'm talking about the ahegao face! Whether you love it or you hate it (i most certainly love it), you have to admit that how it caught on is unique even within meme culture. It is surprising then, that the original use of the term seems pretty much lost to time, and at best the author can only explain how the word and the facial expression converged—because the two were not linked initially.

Summarising though, in terms of Ahegao, as a word, it originated from the world of JAV; whereas, the expression is a variation of the ikigao (facial expression of female climax), which has been around almost as long as the medium. Pretty much the only thing that can be said with certainty is that it was Takeda Hiromitsu (The literal godfather of Ahegao) who has the first published use of the expression that is referred to as ahegao. Knowing that now, I think FAKKU should make a new ahegao t-shirt to commemorate Takeda Hiromitsu contribution to the meme. The dude seriously makes the best ahegao content and we desperately need to get Sister Breeder published.

Chapter Six: "Ramee" isn't a sfx but ok

Chapter 6 covers two onomatopeias that are regular fixtures in manga "Kupaa" and "Ramee". The former relates to a sound that is made when a woman spreads her legs or more specifically when a woman uses her fingers to spread herself open. The latter is a deliberate mispronunciation of "dame" (don't) that was popularised by Nankotsu Misakura who promulgated a whole host of slang terms and unique speech patterns we see all across the medium today. Its effective usage is to describe such intense pleasure that the character is incapable of speaking normally. Frankly, of all of the chapters I've read so far, this is the least interesting, at least from a westerners perspective. While I can read Hiragana and katakana, I rarely pay much attention to the sound effects, and I can only imagine that is the same for most westerners. Likewise, the origins of both terms are again unknown, and the only thing that can be said with certainty is that both exploded in popularity in the 00s, with the rise of widespread internet use—which seems to be the case with all of these.

Chapter Seven: There is value in seeing genitalia — censorship 👠is 👠not 👠an 👠artistic 👠expression ðŸ‘

Chapter 7 discuss the unique problem of censorship within Japan, which is a topic, I think most westerners find quite weird and a little backwards, especially in this day and age. The author also tries their best to frame it as though it is itself an artistic expression, which I found funny because it contradicts comments made by themself and artists. Not to mention the fact that tentacle and the cross-section view were direct attempts to circumvent it out of sheer disdain for the pointless practice.

As a whole though, the rest of the chapter was quite interesting. The author shows the various forms censorship has taken throughout its history, changing with the times. Being particularly bad during the 90s but loosened up in the 00s, only to get worse again following the incident with CORE Magazine back in 2013. They also spend some time explaining how censorship isn't limited to just genitalia. The industry and various explicit and implicit regulations that publishers abide by, and which have affected everything from other aspects of the body; such as nipples, to the sorts of outfits a character can be seen wearing on the cover of different types of publications. It really just goes to show that the wounds of censorship can be self-inflicted, particularly when using a concept such as obscenity as the basis for regulations. As there is no legal definition, its application is inconsistent and at times illogical.

More to come.

Chapter One: Th Evolution of Breasts

Chapter 1 cover the evolution of breast in gekiga works in the 70s, bishojo and lolicon works in the 80s, and then finally into how kyounyu and its various other forms began to take over through the late 80s, and which seemingly culminated in the early 00s. Honestly, it was a pretty interesting chapter. I particularly like the idea of there being kyounyu researchers out there and that the lolicon fundamentalists fought the ero-supremacists over the direction of the medium — totally has ero-opera vibes. It was also pretty interesting to see how—as Kyounyu evolved through the 90s and early 00s—just how many legendary artists who started back then, are still around today; Distance, Yumisuke Kotoyoshi, and Miyabi Tsuzuru to name a few. As well as, just how much we owe to the likes of Kei Kitamimaki and Tohru Nishimaki, who were really the pioneers of kyounuu way back when. The level of influence they've had really can't be measured, particularly Kei Kitamimaki who I've always felt has been underrated. I mean, if it weren't for him, we might never have got marumiya, who is without a doubt, my favourite futanari artist.

Chapter Two: The Dragonball Nipple

Chapter 2 cover the origins of the now-ubiquitous "Nipple Afterimage technique" and how it's become such a dominant tool in an artist's toolkit to convey motion. It's a pretty long chapter if I'm honest, and quite the slog to get through. There are two interviews with the creators of the technique; Hiroya Oku - the creator of Gantz and Hiroyuki Utatane - the creator of Countdown: Sex Bombs. Oku's interview is quite long and you get a certain sense of, firstly; deja vu within similar questions or answers being given, and secondly; a sense that the author is overthinking things somewhat. Coming up for air on the other side though, you then get a rundown of the evolution of the technique from 1988 to the present day. Personally, I'm not really a big fan of the earlier interpretation of the afterimage. In my mind, it only really got good around the early 00s.

Chapter Three: Censorship be damn, you cannot stop the tentacle!

Chapter 3, though short, delves into tentacle rape/play and how the birth of this trope is directly related to Japan's censorship laws. It's probably one of the better chapters. I particularly liked the interview with Toshio Maeda, who I think needs no introduction. Their discussion on the practice of censorship in Japan was interesting, although I was surprised and less than convinced with their argument for maintaining the practice (pg 151). That aside though, following the interview, we get a rundown of the evolution of the trope. From its initial boom in the 80s to its 90s decline, and then its resurgence in the 00s. Hopefully, FAKKU might pick up some tentacles books in the future.

Chapter Four: The confusing history of the cross-section or is it x-ray view?

Chapter 4 covered the cross-section view trope, though rather confusingly. At the start, the author explains the difference between the cross-section, as you might see in a medical journal, and the x-ray or transparent view, as they called it. However, they then go on to show examples of the x-ray view but refer to them as cross-sections, which muddies the waters. That aside though, the history and evolution of the two had some interesting moments. Again it was pointed out that the cross-section view came about to circumvent censorship by framing it as educational and using it predominately for comedic effect. Later in its history, it was adopted into ero-manga, with guro artists taking it to the extreme, whereas less niche genres were more restrained and balanced it more with the x-ray view. The real highlight of the chapter though was the interview with John. K. Pe-ta, who I think straddles the fence between guro and pretty. Honestly, I really enjoy his artwork but at the same time, it can be pretty distressing. It's one of the reasons why his books always start with Monzetsu, which means 'comfy agony'... you can't say he isn't warning people.

Note: in chapter 8 (foreign impact), the author clarifies that what the Japanese call the cross-section view, Americans or westerners call the x-ray view. You may read the chapter and be slightly confused, as I was, but just know it gets clarified later. Personally, I still think their idea of a cross-section view is wrong. To me, you need to have a clear axis that you're slicing down/across. If you're just peering into an object, that to me is just transparent or x-ray.

Chapter Five: Ahegao Face—you either love it or hate it

Chapter 5 covers a topic I think most people would have some interest in, simply because of how it's transcended the medium, going on to have widespread global use. If it wasn't obvious enough already, I'm talking about the ahegao face! Whether you love it or you hate it (i most certainly love it), you have to admit that how it caught on is unique even within meme culture. It is surprising then, that the original use of the term seems pretty much lost to time, and at best the author can only explain how the word and the facial expression converged—because the two were not linked initially.

Summarising though, in terms of Ahegao, as a word, it originated from the world of JAV; whereas, the expression is a variation of the ikigao (facial expression of female climax), which has been around almost as long as the medium. Pretty much the only thing that can be said with certainty is that it was Takeda Hiromitsu (The literal godfather of Ahegao) who has the first published use of the expression that is referred to as ahegao. Knowing that now, I think FAKKU should make a new ahegao t-shirt to commemorate Takeda Hiromitsu contribution to the meme. The dude seriously makes the best ahegao content and we desperately need to get Sister Breeder published.

Chapter Six: "Ramee" isn't a sfx but ok

Chapter 6 covers two onomatopeias that are regular fixtures in manga "Kupaa" and "Ramee". The former relates to a sound that is made when a woman spreads her legs or more specifically when a woman uses her fingers to spread herself open. The latter is a deliberate mispronunciation of "dame" (don't) that was popularised by Nankotsu Misakura who promulgated a whole host of slang terms and unique speech patterns we see all across the medium today. Its effective usage is to describe such intense pleasure that the character is incapable of speaking normally. Frankly, of all of the chapters I've read so far, this is the least interesting, at least from a westerners perspective. While I can read Hiragana and katakana, I rarely pay much attention to the sound effects, and I can only imagine that is the same for most westerners. Likewise, the origins of both terms are again unknown, and the only thing that can be said with certainty is that both exploded in popularity in the 00s, with the rise of widespread internet use—which seems to be the case with all of these.

Chapter Seven: There is value in seeing genitalia — censorship 👠is 👠not 👠an 👠artistic 👠expression ðŸ‘

Chapter 7 discuss the unique problem of censorship within Japan, which is a topic, I think most westerners find quite weird and a little backwards, especially in this day and age. The author also tries their best to frame it as though it is itself an artistic expression, which I found funny because it contradicts comments made by themself and artists. Not to mention the fact that tentacle and the cross-section view were direct attempts to circumvent it out of sheer disdain for the pointless practice.

As a whole though, the rest of the chapter was quite interesting. The author shows the various forms censorship has taken throughout its history, changing with the times. Being particularly bad during the 90s but loosened up in the 00s, only to get worse again following the incident with CORE Magazine back in 2013. They also spend some time explaining how censorship isn't limited to just genitalia. The industry and various explicit and implicit regulations that publishers abide by, and which have affected everything from other aspects of the body; such as nipples, to the sorts of outfits a character can be seen wearing on the cover of different types of publications. It really just goes to show that the wounds of censorship can be self-inflicted, particularly when using a concept such as obscenity as the basis for regulations. As there is no legal definition, its application is inconsistent and at times illogical.

More to come.