An old moral dilemma - The Trolley problem

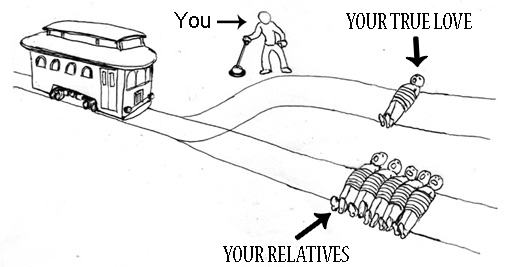

Will you do nothing and let five less important people die or will you hit the switch and let your true love die to save five people at the cost of one?

0

Just assume that the drawing represents your true love and relatives.

¤ That trolley car weighs 7000 kilograms (not including everything inside), which basically means if you jump to save both of them, you just kill yourself and the trolley car still goes on like nothing happened.

¤ Those ropes that you see are the toughest of the toughest and are nailed to the ground. So, No, you can't run and cut the ropes or drag them out of the way.

¤ Those ropes that you see are the toughest of the toughest and are nailed to the ground. So, No, you can't run and cut the ropes or drag them out of the way.

A runaway trolley is headed down a track toward five of your relatives - none of whom are immediate family members. They can’t be warned in time to get out of the way. You are standing near a switch that would divert the trolley onto a siding, but your true love is standing there and can’t also be warned in time.

The question is, could you throw the switch, killing one precious person to save five less precious ones?

(Assume that jumping onto the tracks yourself is not an option.)

EDIT: I made it as simple as possible but since a lot of people think there is no answer or that both are morally evil, or that between A and B, they can choose C (which is to jump) I'll add more detail.

No, this is not a random question that came from my mind, hence, the an old moral dilemma title.

This is a thought experiment in ethics, mostly on the Utilitarian and Consequentialism chapter. This is an example always used in discussions concerning criticisms of utilitarianism, which is the greatest amount of good or happiness for the greatest number of people.

Meaning, if you believe in happiness for the greater number, you have to really think about this question. In a utilitarian perspective, killing your love one (one person) would be not only permissible, but, morally speaking, the better option (the other option being no action at all.)You have to understand, the purpose of the question is to see if "Happiness for the greater number" is really the best thing, not to see who has the greatest talent in poking details.

Dodging the question is one of the things that should always be avoided in philosophy. Many professors or teachers even just directly say "Answer the question" while not giving many details. Rather than choosing to flip the switch, or remain passive, many people will reject the question outright. They will attack the improbability of the premise, attempt to invent third options, or appeal to their emotional state in the provided scenario ("I would be too panicked to do anything",) or some combination of the above, in order to opt out of answering the question on its own terms.

Those who appealed to the unlikelihood of the scenario might appear to have the stronger objection; after all, the trolley dilemma is extremely improbable, and more inconvenient permutations of the problem might appear even less probable.

However, trolley-like dilemmas are actually quite common in real life, when you take the scenario not as a case where only two options are available, but as a metaphor for any situation where all the available choices have negative repercussions, and attempting to optimize the outcome demands increased complicity in the dilemma. This method of framing the problem also tends not to cause people to reverse their rejections.

Ultimately, when provided with optimally inconvenient and general forms of the dilemma, most of those who rejected the question will continue to make excuses to avoid answering the question on its own terms. They will insist that there must be superior alternatives, that external circumstances will absolve them from having to make a choice, or simply that they have no responsibility to address an artificial moral dilemma.

All in all, this means you have to answer the question as it is, not how you want it to be like.

Also, since a lot of people are criticizing the image that I first used, which has a purpose of showing what it looks like, not what the details are, I replaced it.

0

I rather protect the 5 people who are part of my flesh and blood then my true love. Their are plenty of women in the sea and yea I would be devastated for my love but saving part of my family is more important to me.

0

I would divert the trolley.

I... I can't let what would've been only one loss, become a loss for Five different families. [assuming they are all unrelated]

I would do... anything and everything in my power to save everyone... but ultimately, my sense of morality is stronger than my selfish human desires. I've had many precious things taken from me, loved ones included. I've accepted it as a reality of my own life, there's no reason I should let it become someone else'.

Edit: I just realized that I read the OP wrong. If they are non-immediate family members... knowing the the things I know about my family, my answer would be different. Yes.. I'd be far more merciful to 5 strangers than my own family. You don't know my family... they genuinely are just a bunch of morally bankrupt, sick bastards.

I... I can't let what would've been only one loss, become a loss for Five different families. [assuming they are all unrelated]

I would do... anything and everything in my power to save everyone... but ultimately, my sense of morality is stronger than my selfish human desires. I've had many precious things taken from me, loved ones included. I've accepted it as a reality of my own life, there's no reason I should let it become someone else'.

Edit: I just realized that I read the OP wrong. If they are non-immediate family members... knowing the the things I know about my family, my answer would be different. Yes.. I'd be far more merciful to 5 strangers than my own family. You don't know my family... they genuinely are just a bunch of morally bankrupt, sick bastards.

0

Lughost

the Lugoat

Hmmm... I guess I'm the first one to say that I don't think I could divert the trolley. I'm not that close to the vast majority of my family members, and I don't know that I could stand to kill the woman I love. Then again, there's the possibility that after choosing either course of action I go into a deep depression at taking the life/lives of others and commit suicide.

Still though, I think I'd keep the trolley going straight.

Still though, I think I'd keep the trolley going straight.

0

Tegumi

"im always cute"

gizgal wrote...

Well the illustration shows a mere coal cart.I would simply step in its path and stop it.

You're the She-Hulk!

The situation illustrated is silly, idling around on railroad tracks is not something 6 people who aren't brain-addled would do. As for the concept however, I'd probably attempt to save as many people as possible. This is an understandably foolhardy notion and I'd probably die in the process. Or perhaps I'd just be in too much shock to even be able to respond.

0

SD Answer:

Well as we know, theres really no right or wrong answer to this. Both choices have their own moral consequences and im pretty sure each side has its own pros and cons. Personally for me, I think id just randomly flip the switch back and forth as many times as I can until the cart makes a turn or does nothing leaving their fates to chance.

My Answer:

Kill the bitch. Sell the coal. Make money. Get more bitches :D

Weeeeeeeeeee :3 Good night everyone

Well as we know, theres really no right or wrong answer to this. Both choices have their own moral consequences and im pretty sure each side has its own pros and cons. Personally for me, I think id just randomly flip the switch back and forth as many times as I can until the cart makes a turn or does nothing leaving their fates to chance.

My Answer:

Kill the bitch. Sell the coal. Make money. Get more bitches :D

Weeeeeeeeeee :3 Good night everyone

-1

Divert trolley, kill true love with sword! Laugh hysterically because the choice was too hard and now you're insane!

0

luinthoron

High Priest of Loli

Voted do nothing before actually noticing the "not immediate family members" part, but in the end, I would most likely still choose love over the five relatives even in this case.

0

Considering they're not immediate family, kill them, more then likely they'll be annoying in afew years.If my perception of what my true love is correct, she would obviously have more worth than the distant relatives whose only connection to me is as fickle as asking for money.Also, apparently my relatives are deformed and are around 2 feet and a half tall, they wouldn't survive anyways(How fast is this coal cart moving?Even if it was a car that weighs a tonne, more than likely they would just get severe fractures and breaks, for sure concussions, and perhaps the last one would even get pushed off the track by the body mass of the others being sent towards him

0

I'd kill my relatives, can't think of any group of people that would take priority over my loved one.

0

"Hit the trolley 1/2 way so it falls out the track and saves them all."

Too bad its not a option.

Save the girl.

Too bad its not a option.

Save the girl.

0

If it's anything like how the illustration describes, I would just kick the cart and topple it over and risk the leg injury.

0

Data Zero

Valkyrie Forces CO

If possible, i try to stop the trolley. Even if i must die, so be it.

*edit* Why is the guy happy?

*edit* Why is the guy happy?

0

Probably save the 5.

It depends on the situation though (end of the world for example, then I'd save this "love". I'm not into incest).

It depends on the situation though (end of the world for example, then I'd save this "love". I'm not into incest).

0

I'd save my family members.

When situations like this come up hypothetically, I try to go by the number of people rather than the emotions tied to them. However, I have no idea what I'd do in real life. I'd probably choke and run away.

Damn good this is totally implausible.

When situations like this come up hypothetically, I try to go by the number of people rather than the emotions tied to them. However, I have no idea what I'd do in real life. I'd probably choke and run away.

Damn good this is totally implausible.

0

There is no moral answer to this because the question asks us to choose between allowing evil and allowing evil.

If this were a real life situation, then there is another allowed option to throw oneself onto the tracks and try to throw off the trolley from the tracks. The basic premise of the problem though is that you have to choose to allow something to die without any other option. In that case, there is no right move.

If this were a real life situation, then there is another allowed option to throw oneself onto the tracks and try to throw off the trolley from the tracks. The basic premise of the problem though is that you have to choose to allow something to die without any other option. In that case, there is no right move.

0

Lughost

the Lugoat

Daedalus_ wrote...

There is no moral answer to this because the question asks us to choose between allowing evil and allowing evil.If this were a real life situation, then there is another allowed option to throw oneself onto the tracks and try to throw off the trolley from the tracks. The basic premise of the problem though is that you have to choose to allow something to die without any other option. In that case, there is no right move.

But if you had to pick one of the two options provided, which would you choose?

0

Grenouille88 wrote...

But if you had to pick one of the two options provided, which would you choose?

That is not serious discussion; that's just a personal choice.

The question is, could you throw the switch, killing one precious person to save five less precious ones?

The question is phrased poorly. Of course you could.

0

ye I agree, and since it's not specified how related you are to the people they don't really have a fixed value for the group of people. If they had then I think it mainly comes down to how easy people have finding a replacement for their girl/guy, if it's hard they kill their relatives, if it's easy they get kill the girl/guy and get a new one.